The 1st day of God’s work

The light

Day 1, Dome of Genesis. Basilica of San Marco, Venice (13th century). Light shines in the darkness. This is God’s work: to lead mankind from darkness to light. In the text of Genesis, this is God’s first word, expressing his desire to make himself known, to make himself seen, so that humanity, which does not believe in his free love, can see his true face. Above all, it is the spiritual light of God’s love that comes to visit us and dispel our doubts. It is Jesus who agrees to enter Jerusalem, where he will be put to death. It is in his death that humanity will be able to contemplate the glory of God, the immensity of his love and forgiveness.

The first step that leads humanity from darkness to light is the one that gives us a glimpse of the greatest love, the gratuitous love of God, who gives us life because he wants us to discover the joy of loving as he loves. This love takes no account of mistakes or offenses we may commit, but it is ready to forgive, infinitely. When human beings can hope for possible forgiveness, for a gesture of free love, then they glimpse a light in the darkness. (See the article The seven days, stages of love, the first day).

The stages in the life of Jesus

Advent and Christmas

Nativity, mosaic from the Martorana church, Palermo (12th century). A ray of light connects the star to the baby Jesus, emphasizing that he has come to bring light into the darkness, and the Greek text reads: The genesis of Christ, the beginning of the work of salvation for mankind. The donkey and the ox beside him announce the reconciled peoples who come to eat at the same manger, and the little child in the manger already announces that he will nourish the world with his love and his body. The ox, a pure animal according to Jewish tradition, represents Abraham’s descendants by flesh and blood, but Jesus offered his life for all, and it is by faith that we are Abraham’s descendants. Thus, the donkey was considered impure according to Jewish tradition, and represents other people. Jesus came to reconcile all peoples. The shepherds listen to the angels who announce God’s peace on earth.

What the Christian faith proposes to meditate on with regard to the mystery of Christ’s nativity is God’s attitude towards his children. He gave them life so that they could experience the joy of loving and serving one another, and yet human beings are unable to find the path to happiness. Division, rivalry and war reign. Humanity is in darkness, as if blinded, and God, the Father, comes to its rescue, like a good shepherd who comes to lead his sheep. He leads them to still waters, to green pastures. But how does the good shepherd win the trust of his sheep? By showing that he is willing to take any risk for them. So he makes himself weak among creatures, he comes as a child, defenseless. Yet he knows the risks: jealousy, greed and the thirst for power will immediately be his enemies. A king, Herod, senses that this child could undermine his power and makes an attempt on his life. Darkness feels threatened by light, yet God rises to the challenge. In order for the light to shine without end, we must not give in to vengeance or hatred, but show the face of peace, forgiveness and gratuitous love, to the very end.

Holy Week

Entering Jerusalem

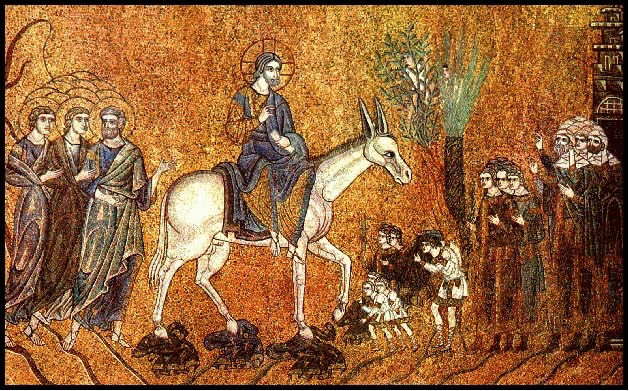

Entry of Jesus into Jerusalem, Ascension dome, mosaic from Saint Mark’s, Venice (12th century). Jesus rode on a donkey, as the prophets had foretold. For Jewish tradition, the donkey is an impure animal, as are people of other religions. But with this gesture, Jesus signifies that God’s invitation to experience his happiness is for all peoples, and that there is no need to distinguish between human beings: we all have a single source of life, and God’s love gives itself to the many.

Jesus’ birth heralds the goal of his mission: to bring light to the world, that is, to show where true happiness lies. Not in passing possessions, but in the love we can offer each other, and a love that consists in giving our own lives for those we love. The offering of one’s own life can be realized in daily service, or in the extreme witness of giving one’s own life, once and for all, in the face of persecution.

Thus, in the Church, for a holy martyr who offered his own life for justice, we celebrate the day of his birth on earth, but also the day of his birth in heaven, i.e. the day of his martyrdom, of his death.

For the Son of God, his birth reveals his will to come to the rescue of humanity, and his entry into Jerusalem, the final resolution, where he freely chooses to give his life. Indeed, he knows, as he announces to his disciples, that if he enters Jerusalem it is to be arrested, condemned to death and resurrected on the third day. Thus, he freely accepts his passion, he accepts to give his life, when he could have saved it by retiring to a quiet, secluded place in Galilee, close to his family. But he knows that to bring light to the world, he will have to show love at its highest level, by offering his own life, so that humanity can feel loved by God, despite its faults, its errors, its mistakes.

The relationship with God and with our neighbor

We see forgiveness

The Nativity. Mosaic by Pietro Cavallini in the church of Sainte-Marie-du-Transtévère (13th century). Through his birth, Jesus came to the rescue of humanity, bringing the light of God’s love into the darkness of a world that could no longer find its way to life and happiness. Like the Samaritan in the parable who finds a wounded man by the side of the road and, after treating his wounds with oil and wine, entrusts him to the care of an innkeeper, leaving him some money. In the same way, Jesus entrusted his disciples to be a reflection of his mercy in this world. That’s why, in this mosaic, we see a house with the inscription “Taberna meritoria”, which not only reminds us of the tavern in the Gospel, but the very history of this church where a tavern once stood. The story goes that, after an oil spring miraculously gushed forth in this spot, Christians bought back the tavern and built a church that served to help the poor in this underprivileged neighborhood.

God comes to the rescue of humanity, and two of Jesus’ parables tell us how he was going to save us. The first is the parable of the Good Samaritan:

[The doctor of the law] said to Jesus, “And who is my neighbor?” Jesus spoke again, “A man was going down from Jerusalem to Jericho, and he came across some bandits; they stripped him and beat him, and went away, leaving him half dead. By chance, a priest was coming down that road; he saw him and passed by on the other side. Likewise, a Levite arrived at the same spot; he saw him and passed by on the other side. But a Samaritan who was on the road came near him; he saw him and was moved with compassion. He went over to him, bandaged his wounds with oil and wine, loaded him on his own horse, took him to an inn and took care of him. The next day, he took out two silver coins, and gave them to the innkeeper, saying, “Take care of him; whatever you’ve spent extra, I’ll pay you back when I come back.” Which of the three, in your opinion, was next to the man who fell into the hands of the bandits?” The doctor of the Law answered, “The one who showed him mercy.” Jesus said to him, “Go and do likewise.” (Luke 10:29-37).

Now, in this image, the artist Pietro Cavallini has depicted, below the crib, the inn to which the Good Samaritan will entrust the wounded man: in fact, next to the house is written “Taberna meritoria”. According to Christian tradition, the Good Samaritan who takes care of the wounded man represents Jesus who comes to the rescue of humanity, afflicted by all manner of evils. He takes care of them and entrusts them to the Church, that is, to those who, having recognized in him the work and presence of God, will be transformed by the sacraments, represented by oil and wine. Believers, disciples of Christ, animated by the same spirit of love, will thus be a reflection of his mercy in this world, and will in turn be able to welcome and care for the suffering, for humanity in distress. This is also made clear at the foot of the image, by the Latin inscription: “Iam puerum iam summe pater post tempora natum accipimus genitum tibi quem nos esse coevum credimus hincque olei scaturire liquamina tybrim”. This formula not only sums up Christian faith in the divinity of Christ, but also tells the miraculous story of the church of Sainte-Marie-au-Trastévère, where the mosaic is located. Indeed, its translation tells us that in this child who was born in our time, we are in fact welcoming the one who is the Father of humanity, and that in this place (this church) a (miraculous) oil arose and flowed down to the dirty water of the Tiber. According to the story of this church, the Christians bought out an old inn that housed soldiers who deserved their retirement because a miraculous oil had sprung up near it, and transformed it into a place of prayer and hospitality for the poor.

If we look again at the mosaic, we also see the good shepherd with his sheep. Jesus’ parable also tells us of his willingness to come to the aid of mankind:

“If one of you has a hundred sheep and loses one of them, does he not leave the other ninety-nine in the desert to go and look for the one that is lost, until he finds it? When he has found it, he takes it on his shoulders, all joyful, and, back home, he gathers his friends and neighbors to say to them, “Rejoice with me, for I have found my sheep, the one that was lost!” I tell you, there will be more joy in heaven over one sinner who is converted than over ninety-nine righteous people who need no conversion.” (Luke 15:4-8). Early tradition tells us that the lost sheep is the whole of humanity, and that God leaves the company of angels, the 99 other sheep, to venture out to rescue the lost one. This is also clearly expressed in another parable Jesus tells those who try to ensnare him:

“The thief comes only to steal, slit throats and destroy. I have come so that the sheep may have life, life in abundance. I am the good shepherd, the true shepherd, who lays down his life for his sheep. The mercenary shepherd is not the shepherd, the sheep are not his: if he sees the wolf coming, he abandons the sheep and flees; the wolf seizes them and scatters them. This shepherd is nothing but a hired hand, and the sheep don’t really count for him.

I am the good shepherd; I know my sheep, and my sheep know me, as the Father knows me, and I know the Father; and I lay down my life for my sheep. I have other sheep too, which are not of this fold: these also I must lead. They will listen to my voice: there will be one flock and one shepherd. This is why the Father loves me: because I lay down my life, in order to receive it anew. No one can take it from me: I give it of myself. I have the power to give it, I also have the power to receive it again: this is the commandment I have received from my Father.” (John 10, 10-18).

In this way, he announces that he will be ready to give his life to prove to humanity the gratuitousness of his love. He is not seeking his own interests, but the happiness and salvation of blinded humanity.

Above, on the right, we also see an angel announcing to one of the shepherds who had come to adore in this child the Messiah, the Son of God: “Nuntio vobis gaudium magnum”, “I bring you good news of great joy”, for those who later recognize the measure of God’s love for his creatures will in turn become shepherds, bringing this good news of God’s love for every human being, to the world, and they in turn will be ready to give their lives for this testimony to God’s infinite love for mankind, even sinful, lost mankind, the same mankind that condemns him to death and yet receives his forgiveness, the gift of his love. Only then can humanity be saved, when a light of hope in God’s unconditional forgiveness opens a breach in the hardened, despairing, lost heart.

Phrase of the Lord’s Prayer

Our Father who art in heaven

Christ’s initials inscribed in the three circles representing the Trinity. Mosaic from the baptistery of Albenga, Italy (6th century). Three concentric circles in different shades of color represent the mystery of the Trinity, within which are inscribed the initials of Christ’s name in Greek. The letter “Khi” resembles an X and the letter “Rho” resembles a P. The other golden letters in the blue background are the alpha and omega, the first and last letters of the Greek alphabet. By this is meant that Christ’s coming into this world manifests the mystery of the love of God who is Father, Son and Holy Spirit and that, as Son of God, he was eternally before the world came into existence through his Word and will continue to be love eternally after the end of time.

This image shows us the mystery of the Trinity. Three different-colored circles, crossed by the sign of Christ, the Christogram, which unites the Greek letters Khi (in the shape of an X) and Rho, the initials of Khristos. This reminds us that the whole of creation is the work of a Trinitarian God, a God whose life is a relationship of love, like that between parents and sons. A love that is gratuitous, benevolent and rich in mercy, this is the love that God offers to his creatures, his own life. We also see in the three circles of the mosaic the letters Alpha and Omega, the first and last of the Greek alphabet: they tell us that everything was made by God before time, that before our time he was, he is and he will be, and he shines his love on the doves, the image of those who look to the heavens, to the one who gives us life, and at the same time see his presence in Jesus Christ, who offered us his life and proved his love. Entering into a filial, trusting relationship with God is an enlightenment, casting a new light on the world: one source of life for all, one people of brothers and sisters. It is then that we dare to say “Our Father”, when our heart has been opened to welcome all creatures as brothers and sisters, that the Kingdom of heaven dwells within us. (On the love of the Triune God, who loves us like a father and is attached to us like a mother to her child, see the article Genesis 1, 2 Ruah – The Spirit of God is feminine).